What are pollinators?

Bearing all this in mind, It may seem surprising that there is no formal benchmark for what constitutes ‘pollinator friendliness’. So, to better understand, we first need to get to grips with the types and needs of our pollinators.

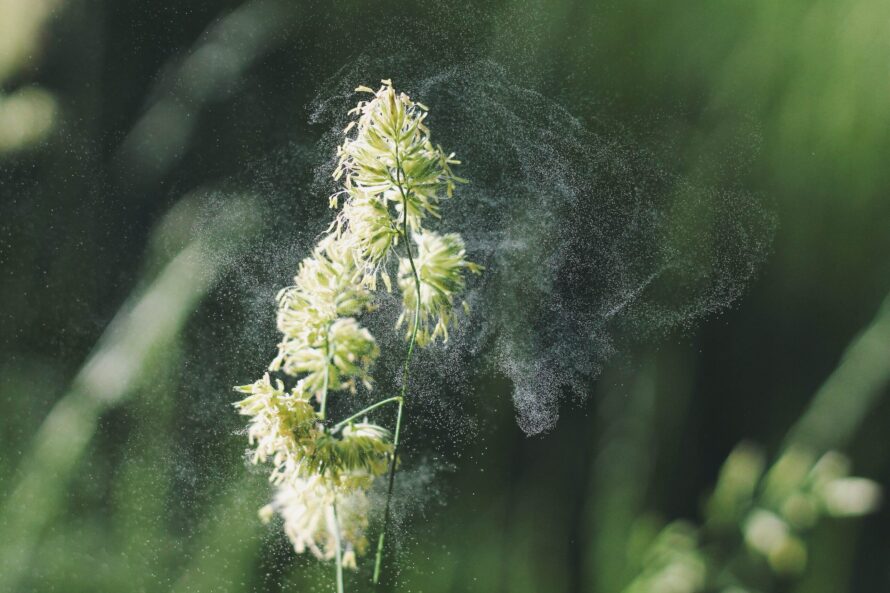

Pollinators are species of animal which move pollen from one flower to another. Globally, this includes species from most terrestrial animal groups, including mammals and reptiles.

When we refer to pollinators in the UK we tend to mean the roughly 1500 species of insect species which pollinate around 80% of our plants. At this point, people often conjure up images of bees and butterflies. In reality, while wild bees are important pollinators, these insects only make up around 20% of our pollinating insect species.

Primary pollinator groups in the UK also include moths, wasps, hoverflies, beetles and other fly species. This is a challenge – how can we ensure that we are friendly to 1500 species, each with their own specific set of ecological requirements and range distributions?