Swift Response by idverde Teams Clears Trowbridge Road After Bin Lorry Fire

In a commendable effort, idverde teams played a crucial role in the cleanup operation

Grounds Maintenance, Landscape Creation, Arboriculture, Sports Surfacing, Parks management, IOS Managing Safely Training, Ecology & Biodiversity, Grass cutting, Horticulture, Street Cleaning, Soft Landscaping, Hard Landscaping

idverde provides a wide range of green services, including grounds maintenance, landscape creation, and advice services, to both private and public sectors across the UK.

We put our first solitary bee box up at Manchester City Football Academy in 2018. Unfortunately, although it was very carefully sited, its location above pitch 14 meant that it became almost forgotten about by MCFC and idverde staff alike. It became weather beaten, had lost its side panels and was infested with woodlice which seemed determined to eat it from the inside-out.

When I came to work at CFA full time in 2020 with the new contract supervisor Dan Banks, we began making a list of jobs for the coming year that would help to increase the biodiversity across the academy site. As well as long grass, wildflower and new pollinator-friendly planting schemes to reinvigorate the shrub beds, a project I singled out was to restore the solitary bee box to its former glory and actually attract bees to nest in it.

Personally, I have always been a huge fan of these boxes because they are just so fascinating, a window into the world of solitary bees and wasps. I knew that given a restorative lick of paint and providing nearby pollen and nectar resources, these nesting boxes would be a fantastic tool to engage staff and site visitors alike, and a way for us to convey the important message of conserving this vitally important guild of pollinators. Infact, I value these habitat enhancing units so much that we secured funding for 2 additional boxes, one to be sited on the elite arc and one to be sited next to the 1st team training pitch.

These nesting units are designed and made by George Pilkington of Nurturing Nature, Birchwood. I have come to know George quite well over the years and he very kindly put me in touch with a client of his from Northampton, who had a surplus of red mason bee cocoons from her garden boxes. Marie sent me 60 cocoons through the post and we put them into the emergence chambers of the CFA boxes in early spring.

Red mason bees (Osmia bicornis) are one of the commonest Spring nesting bees to utilise these nest boxes, the smaller males emerging first in Spring with the larger females about 2 to 6 weeks later. However, we had such a wet spring that many of the males hatched and were killed off by the weather before any females emerged. This could potentially have been disastrous for the new CFA bees. As with all things though, nature seems to find a way and this was the case with the academy red mason bees, with many pairs mating and the females going on to complete nest cells in the solitary bee units.

These nest cells are laborious and complex affairs for the female mason bee. The nest cell is lined with mud, filled with pollen, a single egg is laid and then finally partitioned-off with mud. This is repeated until the female reaches the end of the nest cavity where she will cap the opening closed with a plug of more mud. The eggs hatch into a small grub and feed on the pollen inside its cell until it pupates into an adult bee that will over-winter inside a cocoon that it spins around itself.

One of the most interesting aspects of this solitary bee life-cycle is looking out for all the parasites and parasitoids that are attracted to their nesting behaviour. Individual species of bee will be targeted by a specific species or group of parasites. Amongst others, red mason bees are targeted by a very tiny parasitic wasp in the genus monodontomerus, which will try to infiltrate the mason bee nest cavity and oviposit its eggs into one or more cells. The wasp eggs will hatch quickly and devour the mason bee pollen cache, as well as the mason bee grub itself!

By mid June, the red mason females will largely have completed their breeding cycle, many completing more than one full nesting cavity, and are starting to look very tired indeed. At this point in the year, the males already having died off, their numbers will fall away to nothing. Their place now will be taken by those other fascinating cavity nesters, the leafcutter and yellow-face bees.

With additional investment from MCFC, we were able to purchase summer nesting units. When the first leafcutters begin to emerge, we take the Spring red mason nesting blocks out of the solitary bee boxes and store them over Winter. The cocoons will be removed, cleaned and kept safe until they can be put back out again next Spring, when the whole cycle can start over again. The Summer units have larger 8mm diameter nesting holes for leafcutters and very small 3-5mm diameter nesting holes for yellow-face bees and tiny parasitoid wasps.

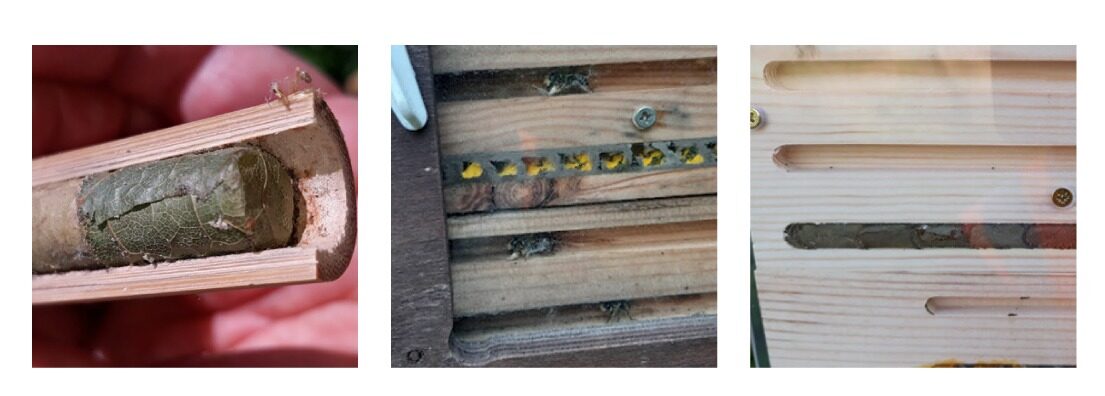

We have two frequently common leafcutter Spp at CFA, Brown-Footed Leafcutter (Megachile Versicolor) and Willughby’s Leafcutter (Megachile Willughbiella). Almost immediately, one of these species has started nesting in the new units (time will reveal which one) but hopefully there is time for many more nests to be completed. Female leafcutters use their sharp mandibles to cut perfectly round holes from the leaves of preferred shrubs (Rose is popular, in my garden they use Pyracantha). They will then use these discs to form a cigar-like cell which the female provisions with pollen, lays an egg and seals with more cut leaves. The accuracy and precision of this procedure cannot be overstated, with each cell interlocking with the next. Leafcutter bees are targeted by sharp-tailed bees in the genus Coelioxys, which will try to breach the leafcutter nest to lay its own eggs there. The sharp-tailed bee grub will then go on to devour the leafcutter pollen supply and larvae.

As well as the Leafcutters that have started using the nesting boxes, we also have some tiny (approx 5mm long) yellow-face bees nesting. Yellow-face bees are different to other bees in that they do not carry pollen back to the nest on their pollen-brushes; instead they carry it back inside their stomachs where it is mixed with nectar and regurgitated inside the nest cell. A single egg is laid which will hatch into a grub and feed on this nectar/pollen solution as it pupates into an adult bee. The female yellow-face bee lines and caps her nest cells with a waterproof, cellophane-like substance that she produces in her stomach.

Yellow-face bee nests are parasitized by the impressive-looking wasp Gasteruption jaculator, which uses its long ovipositor (egg laying tube) to pierce the cellophane-like nest capping of the yellow-face bee and deposit an egg inside its nest.

On a recent site visit, George Pilkington pointed out to us that as well as the red mason bee (Osmia bicornis) nesting in our boxes, we also had the orange-vented mason bee (Osmia leaiana) nesting alongside. This was obvious to a man of George’s considerable experience, as these 2 species line their nest cavities in different ways.

Red mason’s line and cap their cells with mud, but orange-vented bees line and cap their cells with a masticated (chewed-up) leaf-pulp which has an altogether greener look. This was a great surprise to me personally as I have never come across the orange-vented Mason bee at CFA previous to this.

We also had a site visit from Karen McCartney recently. Karen is the South Lancashire (VC 59) recorder for bees and wasps which also covers Greater Manchester. I was showing Karen our solitary bee nesting boxes and describing the success we had already had this year when we spotted what appeared to be a very unusual looking nest cell. This nest cell was lined with a clear substance that superficially resembled a yellow-face bee nest, but this cell was completely filled with cached aphids.

On referring this to George, who keeps meticulous records about all the species that have been known to use his nest boxes, he told me that this was probably the work of a tiny aphid-hunting wasp in the genus Passaloecus. The females provision their nest cells with aphids that she partially paralyzes by seizing them around the neck. She will then cap her nest cavity with a plug of pine resin. The 3 common UK Spp of Passaloecus are not readily identifiable without powerful magnification. Interestingly, Passaloecus gracilis and Passaloecus insignis are both active hunters of aphids; The other, Passaloecus corniger, actively seeks out the nests of the other 2 Spp and plunders their nests of the aphids they have cached away, rather than do its own hunting, (Yeo & Corbett, 1995).

Through the use of these solitary bee nesting units, not only are we able to study familiar species more closely, we are also attracting new invertebrate species to CFA (4 genus and possibly 6 or more species, not to mention associated parasitoids), with the possibility of taking a peek inside their daily activities and monitor their nesting behaviours. There are very few other ways of achieving something like this in a grounds/garden environment. Above all, I believe viewing the day-to-day activities of these engaging invertebrates gives people not only a new understanding of our native insects, but helps to promote a new respect for these industrious, beneficial and fascinating pollinators.

To find out more about idverde’s commitment to ecology and biodiversity, read more here.